WEDNESDAY, July 20 (HealthDay News)– An experimental drug for treating Alzheimer’s disease that previously showed troubling side effects may actually be safe in the long run, researchers report.

The keys to the safety of the drug, bapineuzumab, may be lowering the dose and not giving it to patients with ApoE4, a gene mutation linked to Alzheimer’s, according to two studies scheduled for presentation Wednesday at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease in Paris.

“The data from the open-label trial are encouraging. Patients were able to tolerate bapineuzumab for two to four additional years without the emergence of any new safety concerns,” said Dr. Stephen Salloway, author of one of the studies. “This is important because we are conceptualizing this drug as a long-term treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.”

Encouraging does not translate into certainty, however, another expert pointed out.

“I think it is too early to tell from the data from this small Phase 2 safety trial,” said Ian Murray, an assistant professor of neuroscience and experimental therapeutics at Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine in College Station. “We will have to wait for larger trials to comment on this as a potential therapy.”

The studies were funded by Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy.

Although bapineuzumab has shown promise in certain Alzheimer’s patients, other research found that patients taking a higher dose of the drug had an increased risk of brain inflammation from water retention. This resulted in headache, memory loss, hallucinations, reduced coordination or other symptoms. But no problems were seen with lower doses.

Bapineuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody, which binds to and might be able to eliminate beta amyloid peptide in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Most experts believe that the build up of beta amyloid proteins, which accumulate as plaque, is responsible for Alzheimer’s.

Salloway’s study looked at the drug’s safety in 194 Alzheimer’s patients, most of whom had mild- to-moderate Alzheimer’s and participated in a long-term (78 weeks or longer) study. Some of the participants were followed for four years or more.

Ninety-one percent of participants had side effects, about a quarter of which were attributable to bapineuzumab. Of these, 85 percent were mild or moderate.

The overall rate of vasogenic edema (water on the brain) was 9.3 percent, a number that decreased over time, said Salloway, a professor of neurology and psychiatry at Alpert Medical School of Brown University and director of the Butler Hospital Memory and Aging Program in Providence, R.I. The edema was symptomless in most cases, he said.

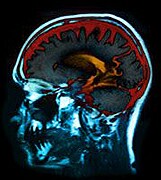

The other study, which involved looking at more than 2,000 MRI scans from 262 patients, found 36 cases of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) may have been linked to the bapineuzumab.

These imaging abnormalities may indicate inflammation of the brain caused by water retention.

But only 8 of those 36 cases involved symptoms, and they were more likely to be found in patients with APOE-e4 who were taking higher doses of the drug. The likelihood of these effects diminished with additional infusions of lower-dose bapineuzumab.

“There is a growing sense that VE [vasogenic edema] or ARIA [amyloid-related imaging abnormalities] is a manageable side effect and may actually be a sign that the drug is clearing amyloid from the brain and the blood vessels,” said Salloway. “Treatment will require ongoing monitoring with MRI.”

The researchers, who said monitoring of bapineuzumab will continue, are now awaiting the results of a larger Phase III trial on the drug.

Because this study was presented at a medical meeting, the data and conclusions should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

The Alzheimer’s Association has more on this condition.