THURSDAY, Jan. 6 (HealthDay News) — A blood test that screens for antibodies, a protein produced by the immune system, may one day be used to detect Alzheimer’s and other diseases, new research suggests.

Though the research is still in its infancy, being able to detect Alzheimer’s via antibodies would be a simpler and less invasive method of diagnosing the disease, researchers said.

But the study’s lead author stressed that the true benefits of such a test for Alzheimer’s patients won’t really arise until scientists develop effective treatments against the disease.

“It’s unclear whether people would want to know a couple of years ahead of time they are going to get Alzheimer’s if they can’t do anything about it,” said Thomas Kodadek, a professor of chemistry and cancer biology at The Scripps Research Institute in Jupiter, Fla. “But I can say with some certainty that we will never get a good therapy for Alzheimer’s without early diagnosis.”

The study, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, is published in the Jan. 7 issue of Cell.

Typically, in developing blood tests for diseases, researchers have searched for antigens — that is, proteins from a virus, bacteria or other disease process such as cancer or neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s — that set off an immune response.

Only after identifying the antigen would researchers then search for antibodies to that antigen, or signs that the immune system had picked up on the problem and mounted a response.

But antigens can be difficult to find, Kodadek explained.

“In Alzheimer’s, or in a disease such as cancer, it’s not at all obvious what the initiating event is,” he said. “We just don’t know what are those first weirdly modified proteins that are unique to the disease process that the immune system ‘sees.'”

The new research went about things differently. Rather than search for the elusive antigen, researchers did “high throughput” screening using thousands of synthetic molecules, called peptoids, that would bind with the antibodies.

Comparing blood samples from six Alzheimer’s patients, six healthy people and six Parkinson’s disease patients, the researchers found that two of the thousands of synthetic molecules “captured” at least three-fold more immunoglobulin (IgG) antibodies from all six of the Alzheimer’s patients than from either the healthy controls or the Parkinson’s patients.

The synthetic molecules, in effect, acted as a lure for the antibodies — enabling the researchers to spot biomarkers in the blood unique to those with Alzheimer’s.

This process could be repeated to test for antibodies associated with other diseases as well, Kodadek theorized.

“The big advance from what people have been doing before is that this method completely removes the requirement of knowing the native antigens that triggered the immune response,” Kodadek said. “The real excitement is it should allow us to identify biomarkers for any disease for which the immune system reacts.”

The synthetic molecules are easily modifiable and can be produced quickly in large quantities at lower cost, Kodadek said.

However, while promising, the results are preliminary and need to be replicated in larger numbers of patients, noted Dr. Jeremy Koppel, an Alzheimer’s research scientist at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y. He was not involved in the new research.

“This study represents a novel approach to the development of a noninvasive screening instrument for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, which currently lack definitive diagnostic biomarkers,” Koppel said. “Beyond diagnostics, the future identification of the biomarkers detected in this study has the potential to deepen our understanding of the disease process itself.”

Another caveat is that the study was done in people who already had Alzheimer’s, not those merely at risk for the disease. Further research needs to be done to determine how soon into the progression of the disease the abnormal antibodies can be detected.

Right now, there are a few medications that can help with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, but there are no treatments that slow the progression of the disease.

So for many patients, early diagnosis may not necessarily be something they want, Kodadek said. But from a research perspective, early diagnosis is a key to developing better treatment, he added.

With neurodegenerative diseases, the hope is that drugs could block further decline, making it crucial to know if a person has the disease before they begin having significant symptoms, he said.

More information

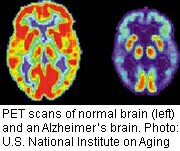

The U.S. National Institute on Aging has more on Alzheimer’s.