THURSDAY, Dec. 26, 2013 (HealthDay News) — Older adults with memory problems and a history of concussion have more buildup of Alzheimer’s disease-associated plaques in the brain than those who also had concussions but don’t have memory problems, according to a new study.

”What we think it suggests is, head trauma is associated with Alzheimer’s-type dementia — it’s a risk factor,” said study researcher Michelle Mielke, an associate professor of epidemiology and neurology at Mayo Clinic Rochester. “But it doesn’t mean someone with head trauma is [automatically] going to develop Alzheimer’s.”

Her study is published online Dec. 26 and in the Jan. 7 print issue of the journal Neurology.

Previous studies looking at whether head trauma is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s have come up with conflicting results, she noted. And Mielke stressed that she has found only a link or association, not a cause-and-effect relationship.

In the study, Mielke and her team evaluated 448 residents of Olmsted County, Minn., who had no signs of memory problems. They also evaluated another 141 residents with memory and thinking problems known as mild cognitive impairment.

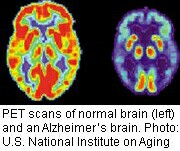

More than 5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Plaques are deposits of a protein fragment known as beta-amyloid that can build up in between the brain’s nerve cells. While most people develop some with age, those who develop Alzheimer’s generally get many more, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. They also tend to get them in a predictable pattern, starting in brain areas crucial for memory.

In the Mayo study, all participants were aged 70 or older. The participants reported if they ever had a brain injury that involved loss of consciousness or memory.

Of the 448 without any memory problems, 17 percent had reported a brain injury. Of the 141 with memory problems, 18 percent did. This suggests that the link between head trauma and the plaques is complex, Mielke said, as the proportion of people reporting concussion was the same in both groups.

Brain scans were done on all the participants. Those who had both concussion history and cognitive [mental] impairment had levels of amyloid plaques that were 18 percent higher than those with cognitive impairment but no head trauma history, the investigators found.

Among those with mild cognitive impairment, those with concussion histories had a nearly five times higher risk of elevated plaque levels than those without a history of concussion.

The researchers don’t know why some with concussion history develop memory problems and others do not.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, among several other supporters.

The study adds valuable information for experts in the field, said Dr. Robert Glatter, director of sports medicine and traumatic brain injury in the department of emergency medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital, in New York City. Glatter, who is also a former sideline physician for the National Football League’s New York Jets, reviewed the new study findings.

Other studies, he said, often rely on postmortem information. In the Mayo study, participants had to have loss of consciousness as a measure of having a concussion history, Glatter noted. However, he added, the new thinking is that loss of consciousness is not necessary to define a concussion — one can occur without that.

The effect of head injury may be cumulative over time in the development of Alzheimer’s, he said. In the past, experts thought only severe head trauma was linked with Alzheimer’s, but less severe injury may actually be relevant as well, he added.

Some other factor or factors yet to be discovered may be at play, Glatter said.

Both Mielke and Glatter stressed that concussions don’t automatically lead to Alzheimer’s. “Not all people with head trauma develop Alzheimer’s,” Glatter said.

“If you do hit your head, it doesn’t mean you are going to develop Alzheimer’s,” Mielke said, although “it may increase your risk.”

More information

Learn more about the brain from Harvard University’s Whole Brain Atlas.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.