THURSDAY, Dec. 22 (HealthDay News) — Late December wouldn’t be the same without the uplifting sound of holiday choirs, but there’s a unique chorus in New York City, called “The Unforgettables,” that’s bringing new harmony to singers and audiences alike.

That’s because the chorus’ 22 members include 11 men and women diagnosed with early to middle-stage dementia, including dementia linked to Alzheimer’s disease, paired up with 11 of their caregivers — a spouse, child or friend.

Each practice and recital is an act of togetherness and renewed strength in the face of illness, one of the chorus’ founders said.

“The pleasure this process has given participants was clear from the start,” said researcher Mary S. Mittelman, who spearheaded the choir’s inauguration back in June, along with colleagues from the NYU Langone Medical Center’s Center of Excellence on Brain Aging. “The chorus has proven to be a wonderful place to be, where no one feels stigmatized.”

Organizers say this is the first choir of its kind in the United States. Patients and caretakers were initially recruited through outreach that involved a number of local organizations, including the New York City chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association and Langone. The chorus currently includes people diagnosed with either Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia called Lewy body disease.

Chorus members meet once a week to practice and are joined by musicians who serve as conductor-directors. They’re taught standard techniques to enhance breathing, vocalization and performance, just like any other choir, Mittelman said.

To date, two public performances have been staged: The first, in September, featured 18 songs ranging from classical to folk to pop; the second, which took place just last week, was filled with holiday favorites.

“There’s a certain camaraderie,” noted Howard Smith, a choral member who cares for his wife, Lois, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s about two years ago. “Lois is there with people with the same problems. And it’s comforting for her and the other patients, and even for the caregivers. Because it means we’re not alone.”

That sense of inclusiveness is key, Mittelman agreed. Too often, she said, the typical caregiver is “afraid to go to a normal event with a person with dementia. And so he ends up being discounted, or discounts himself, as people exclude him from social events and he has less and less activities to participate in and becomes more and more isolated.”

That means that a group such as The Unforgettables becomes “very important,” said Smith, a painter and CUNY professor who commutes from the Hudson River Valley to join rehearsals with his wife each week. “Here you get a group like this together and it’s not threatening.”

Could the choir experience have therapeutic value, too? Mittelman says that’s not been proven, but she hopes music may be an “unexplored opportunity” for improving cognitive function.

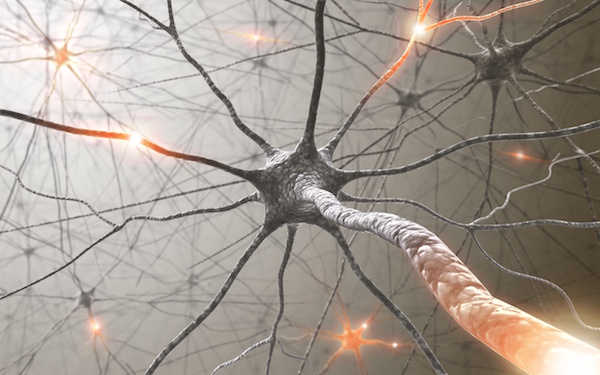

“Who’s to say that singing in this chorus isn’t having a really positive effective on mental function?” she asked, pointing to prior research that’s indicated that exposure to music may elicit profound motor responses in every region of a patient’s brain, stimulating the release of neurotransmitters and endorphins while triggering musical and emotional memory.

Delving further, Mittelman said she’s now incorporated The Unforgettables into, “a research project with structured assessments before, in the middle and after the concert, as well as focus groups, to assess the benefits of participating.”

One outside expert believes it may be worth studying. This kind of choral project, “may very well have a profound impact on the quality of life of both patient and family,” said Dr. Robert Friedland, chair of neurology at the University of Louisville School of Medicine, in Kentucky.

“I actually believe it has a wonderful potential to be an Alzheimer’s therapy,” he said. “First, it involves physical activity, which is good for the brain and the heart. You have to get up and go. You can’t participate in the activity if you stay home. And then singing involves emotional and social relationships, which are stimulating. And it provides purpose, so it’s a meaningful activity and a very vigorous one. And it also would be a valuable approach to dealing with depression, which often accompanies dementia.”

“That’s not to say,” Friedland cautioned, “that it’s proven that singing in itself is effective as a therapy. But there’s every reason to believe that it may very well be.”

For his part, Smith says he doesn’t need a study to know that the chorus is improving the quality of life for members, allowing them to regain their dignity.

“For example, there’s a guy in the group, Chester, who is rather advanced in terms of his situation,” Smith said. “Now this is a man who worked for IBM. He was very, very bright and educated. But when he was asked to [join the chorus], even clapping was very difficult for him. And yet now he is performing a solo in the concert from ‘Fiddler on the Roof.'”

“I think there is a realization that the participants with dementia still have some behavioral skills working,” he explained. “One watches loved ones or friends unable to accomplish tasks, having difficulty processing or retaining thoughts, or just experiencing confusion. And all of a sudden [in the chorus] they are functioning in a group setting and succeeding in singing words and melody.”

More information

There’s more on how music impacts dementia care at the Alzheimer’s Association.