TUESDAY, July 17 (HealthDay News) — An immune-based drug therapy using blood plasma antibodies has stalled the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in a small group of patients receiving the therapy over three years.

A phase 2 trial carrying 16 of 24 participants from an earlier study suggested a slower-than-expected deterioration in their thinking abilities, behavior and daily function with twice-monthly infusions of intravenous immunoglobulin, or IVIg. Four of the patients who had received a standardized dose throughout the 36 months showed no decline on standard measures of cognition, memory, daily functioning and mood.

“When [Alzheimer’s patients are] untreated, there are typically measurable declines every three to six months . . . so for four to be stable over a three-year period is very much unexpected,” said study author Dr. Norman Relkin, director of the Weill Cornell Memory Disorders Program, in New York City. “And while that’s not enough to say this is an effective drug, it is encouraging. There have been so many disappointments, I don’t want to create false hope, but I’m very encouraged.”

Relkin is expected to present his findings Tuesday at the annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association, in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Alzheimer’s disease affects about 5 million Americans, with an estimated 35 million worldwide suffering from dementias that encompass Alzheimer’s. Current treatments, including donepezil (Aricept) and memantine (Namenda), sometimes ease symptoms temporarily, but nothing on the market can halt or cure the devastating condition.

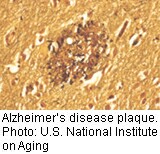

IVIg, known by the brand name Gammagard and already used clinically to treat certain immune deficiencies, cancers and autoimmune disorders, is thought to slow down or prevent the buildup of toxic beta-amyloid proteins, which cause the sticky brain plaques that distinguish Alzheimer’s.

Infusions with IVIg demonstrated a sliding scale of effectiveness in the 16 patients. Five participants who initially were treated with an inactive placebo and then switched to IVIg experienced decline while on placebo but showed a less rapid decline after 18 months of IVIg infusions. Eleven patients who received varying doses of IVIg experienced more favorable outcomes, with the best results among the four patients treated with a specific standardized dose (totaling 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight) every two weeks for the duration of the study.

“I think this is really exciting, but the numbers are very small,” said Catherine Roe, an assistant professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “We just need more [patients] and more time. I really hope the results pan out over the long term.”

Relkin is in the midst of a phase 3 trial of IVIg with about 400 participants and expects to release results early next year. He predicted that some Alzheimer’s patients and their doctors would seek IVIg as an “off-label” treatment since it is already available commercially.

But the therapy doesn’t come cheap: Treating Alzheimer’s with IVIg would likely cost between $2,000 and $5,000 every two weeks, with higher doses (and costs) reserved for heavier patients, Relkin said.

His current phase 2 trial indicated that the treatment is well-tolerated by patients (minor side effects included rash, chills and headache) and the drug already has a well-established safety profile, he noted.

“I think this gives us a clear direction in terms of our efforts to develop better, more effective and less costly treatments,” Relkin said. “Right now, as a field we’ve been floundering for that direction. Most importantly, the impact of the study would give us a clear Achilles’ heel for Alzheimer’s — something we can target and use to alter the underlying disease course.”

Because this study was presented at a medical meeting, the data and conclusions should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

The American Health Assistance Foundation has more information on Alzheimer’s-related amyloid plaques.