TUESDAY, Nov. 6 (HealthDay News) — A small study suggests that stem cells can help repair the damage of a heart attack, and it doesn’t matter if the cells originate with the patient or a stranger.

The study, which involved just 30 patients, is the first involving a certain type of cells, called mesenchymal stem cells, that compares outcomes depending on whether the cells came from the patient or a donor.

Across most measures — including reductions in cardiac scar tissue, patient quality of life and safety — people got the same benefit regardless of where the stem cells came from, researchers reported Monday at the annual meeting of the American Heart Association in Los Angeles. The study is also being published online Nov. 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“We believe the basic message of the study is that this procedure is safe and that future, larger studies are warranted,” lead study author Dr. Joshua Hare, director of the Interdisciplinary Stem Cell Institute at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, said at a news briefing.

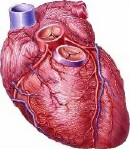

Millions of people around the world suffer from heart failure, often caused by a heart attack that severely damaged heart muscle at some point in the past. This can cause hearts to become enlarged and weakened, a condition called ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Unfortunately, progress against heart failure has been stalled for decades. But recently, scientists have been introducing stem cells, which can turn into cardiac cells, into the hearts of these patients, to see if they might repair the damage.

In most cases, the cells have been sourced from the patients themselves, but that presents its own problems. Speaking at the news briefing, Stefanie Dimmeler, head of the section of molecular cardiology at the University of Frankfurt, Germany, explained that it takes up to two months to grow the millions of stem cells needed for transplant. If a patient suffers a heart attack and needs them quickly, it is just not feasible to use his or her own cells.

“So,” said Dimmeler, who was not involved in the new study, “it might be interesting to have cells ‘off-the-shelf'” that were grown earlier, using an outside donor’s cells.

But would these donor cells perform as well as the patient’s own?

In the new study, Hare and his colleagues investigated that question with 30 patients who all had damaged, enlarged hearts due to a prior heart attack. Half received infusions of their own mesenchymal stem cells, while the other half received cells sourced from young, healthy donors. The patients were then tracked for 13 months.

While the amount of cardiac scar tissue typically does not change for heart failure patients, Hare said that on CT scans “we saw a 33 percent reduction in scar tissue in both [the donor and self-sourced] groups.” Swollen, misshapen hearts also began to change back to a healthier, spherical shape, indicating that scar tissue was receding, he said.

According to Hare, all of this “is very important because we think that this is the basis by which this therapy is going to work.”

Patient function also seemed to improve, regardless of where the cells were sourced from. In terms of quality-of-life scores, “there was an improvement in both groups that was clinically meaningful,” Hare said. Patients from both groups improved at similar rates on a special six-minute-walk test, for example.

Finally, the use of donor stem cells appears to be safe: only one patient out of 30 had any immune reaction to the procedure, and that reaction was “at a very low level,” Hare said.

Still, Dimmeler stressed that, though encouraging, more and much larger trials are needed, and those could take years.

“I think it is still early days,” she said. “Although we are having [stem] cells in the clinic being tested, it’s all so far at very small patient numbers.”

More information

Find out more about heart failure at the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.