TUESDAY, Nov. 13 (HealthDay News) — For black Americans suffering from heart disease, meditation might help prevent heart attacks, strokes and early death, a small new study suggests.

These benefits appear to be the results of meditation’s ability to lower blood pressure, stress and anger, all of which have been linked to increased cardiovascular risk, researchers say.

“This is a whole new physiological effect on top of conventional treatment,” said lead researcher Dr. Robert Schneider, director of the Institute for Natural Medicine and Prevention in Fairfield, Iowa. “People can prevent heart disease reoccurrence using their own mind-body connection. People have this internal self-healing ability.”

An outside expert, however, said the study is too limited in size and scope to allow conclusions as to whether meditation really reduces risk of death or disease.

The new study focused on Transcendental Meditation. Originally from India, it is not associated with any particular religion or philosophy. It is thought to produce alpha brain waves that occur in deep relaxation. According to the Maharishi Foundation, more than 5 million people worldwide practice this type of meditation.

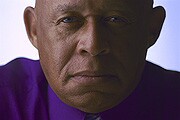

The research focused on blacks because they are at a higher risk than whites of having heart attacks and strokes and dying from heart disease, Schneider said. He added, however, that meditation would work as well among whites and other populations.

“Other studies have been done among whites and the results are similar,” he said.

The report was published in the Nov. 13 issue of the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The study was sponsored by the Maharishi University of Management and funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

For the study, Schneider’s team randomly assigned 201 black Americans with heart disease either to a Transcendental Meditation stress-reducing program or health education class about lifestyle modification in diet and exercise.

Almost 60 percent of the participants were taking cholesterol-lowering drugs. Forty-one percent of the meditation group took aspirin, as did 31 percent of the health education group; 38 percent of the meditation group and 43 percent of the health education group smoked, the researchers noted.

Participants’ average body-mass index — a measurement of body fat based on height and weight — was 32, which is considered obese.

Meditation consisted of sitting with eyes closed for about 20 minutes twice a day. The goal was to rest while remaining alert.

After more than five years of follow-up, the researchers found those who meditated saw significant reductions in blood pressure and anger compared to those receiving health education. In addition, 20 people in the medication group had a heart attack or stroke or died, compared with 32 in the health education group.

Both groups increased exercise and drank less. For those who meditated, there was a trend toward reduced smoking; however, this was not statistically significant.

Learning how to do Transcendental Meditation isn’t inexpensive. An initial 10-hour course runs about $1,500 when taught by nonprofit groups, and there is continued lifetime follow-up, Schneider said.

And it’s not something you can learn by yourself. “You’ve got to have a teacher right there in front of you teaching according to experience,” he said. “So it’s only learned live.”

Transcendental Meditation is not generally covered by health insurance, he said. “One of the reasons we did the study is because insurance and Medicare calls for citing evidence for what’s to be reimbursed,” Schneider said. “This study will lead toward reimbursement. That’s the whole idea.”

But a cardiology expert said that although the study adds to evidence supporting meditation, it doesn’t prove a cause-and-effect relationship between the practice and better health outcomes.

“Transcendental Meditation has been reported to have health benefits and has been evaluated in a number of studies,” said Dr. Gregg Fonarow, professor of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Some studies have suggested favorable effects on cardiovascular risk factors whereas others studies have been inconclusive, he said.

Even though the findings in this study were statistically significant, the new study was too small to be conclusive, Fonarow said.

“In addition, since this study was conducted at a single center and the primary [change in heart attack, stroke and death] was not statistically significant without adjustment for other factors, more studies and replication of these findings are needed,” he said.

More information

For more information on heart disease, visit the American Heart Association.