THURSDAY, Sept. 15 (HealthDay News) — Long-term alcohol abuse can result in significant damage to the brain, a new study shows.

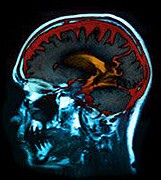

Researchers report that the extent of injury to the brain can be determined by measuring cortical thickness. The more people drink, they noted, the worse the damage.

“We now know that alcohol has wide ranging effects across the entire cortex and in structures of the brain that contribute to a wide range of psychological abilities and intellectual functions,” study corresponding author Catherine Brawn Fortier, a neuropsychologist and researcher at the VA Boston Healthcare System and Harvard Medical School, said in a Harvard news release.

“This is the first study to precisely measure the variation in the thickness of the cerebral cortex, which is the thin layer of neurons that one sees on the surface of the brain and supports all higher-level human cognition,” she said.

Excessive consumption of alcohol has harmful effects on both types of tissue that support brain function, known as white and gray matter. Alcohol’s most significant impact, however, is on the frontal and temporal lobes — areas of the brain critical to learning, impulse control and other complicated human behaviors, the researchers pointed out in the news release.

“In other words, the very parts of the brain that may be most important for controlling problem drinking are damaged by alcohol, and the more alcohol consumed, the greater the damage,” explained Fortier.

In conducting the study, the researchers compared the high-resolution structural magnetic resonance scans of 31 former drinkers and 34 non-drinkers and measured cortical thickness.

“Previous studies were only able to compare large brain regions,” said Fortier, “whereas this method allowed us to look at areas as small as a tenth of a millimeter and compare them across the entire brain. This approach allowed us to identify very subtle but significant alcohol-related damage across the entire brain, revealing two primary findings.”

First, the study found reduced cortical thickness among the recovered alcoholics. Secondly, alcohol’s effects on the brain are determined by how much people drink. Essentially, they showed, the more a person drinks, the greater the damage to their brain.

“This study documents, for the first time, the dynamic nature of the neuropathology associated with chronic heavy alcohol use,” Terence M. Keane, associate chief of staff for research & development at the VA Boston Healthcare System and assistant dean for research at Boston University School of Medicine, explained in the news release. “The results may explain why alcoholism may be so difficult to treat: alcohol damages the very neural systems that are critical to achieving and maintaining abstinence.”

The study authors added that even when they stop drinking, former alcoholics can suffer impaired abilities and personality changes due to alcohol’s effects on the brain.

“Severe reductions in frontal brain regions can result in a dramatic change to personality and behavior, taking the form of impulsivity, difficulty with self-monitoring, planning, reasoning, poor attention span, inability to alter behavior, a lack of awareness of inappropriate behavior, mood changes, even aggression,” added Fortier. “Severe reductions in temporal brain regions most often result in impairments in memory and language function.”

The findings should help doctors better advise and treat their alcoholic patients, the researchers concluded.

“I think what is most important for other medical professionals to know and pass on to their patients is that alcohol misuse is not without consequences,” concluded Fortier. “Not only is the brain impacted, but the very brain structures that are the most impacted are the ones that you need to change problematic behavior. However, it is also important to note that although brain tissue is compromised by alcohol, it can recover to some degree with maintained abstinence. This could be a motivational factor in maintaining sobriety,” she added.

The study is available online and will be published in the December print issue of Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more about the harmful effects of binge drinking.