TUESDAY, Oct. 16 (HealthDay News) — Two weeks of abstinence from drinking can reverse damage to the brain caused by chronic alcohol abuse, according to a new study.

However, recovery may vary among different parts of the brain.

The findings may offer new hope to recovering alcoholics, say authors of the study appearing online Oct. 16 and in the January 2013 print issue of Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research.

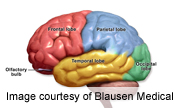

“Shrinkage of brain matter, and an accompanying increase of cerebrospinal fluid, which acts as a cushion or buffer for the brain, are well-known degradations caused by alcohol abuse,” Gabriele Ende, a professor of medical physics in the neuroimaging department at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Germany, said in a journal news release. “This volume loss has previously been associated with neuropsychological deficits such as memory loss, concentration deficits and increased impulsivity.”

Several processes in drinking and abstinence periods likely lead to changes in brain tissue volume, a study co-author explained.

“One process likely reflects true, irreversible neuronal cell death, while another process likely reflects shrinkage, a mechanism that would allow for volume changes in both negative and positive directions, and could account for brain volume recovery with abstinence,” Natalie May Zahr, a research scientist in the psychiatry and behavioral sciences department at Stanford University School of Medicine, said in the news release.

The study examined 49 alcoholics from an inpatient alcohol-withdrawal treatment program — 40 men and nine women. Researchers compared this group to 55 similar people who were not alcohol abusers.

All of the participants underwent a brain scan within 24 hours of detoxification. A second scan was performed after two weeks of supervised abstinence.

“We found evidence for a rather rapid recovery of the brain from alcohol-induced volume loss within the initial 14 days of abstinence,” Ende said.

The study also showed the drinkers had a volume reduction of the cerebellum at the time of detoxification. “This has rarely been observed in other studies at later time points after alcohol withdrawal,” Ende noted. “Two weeks after detoxification, this cerebellum reduction was nearly completely ameliorated.”

Ability to recover from chronic alcohol abuse was better in some parts of the brain than others.

“The function of the cerebellum is motor coordination and fine-tuning of motor skills,” said Ende. While the new study didn’t measure recovery of these skills, she said, “it is striking that there is an obvious improvement of motor skills soon after cessation of drinking, which is paralleled by our observation of a rapid volume recovery of the cerebellum.”

However, she added, “Higher cognitive functions like divided attention, which are processed in specific cortical areas, take a longer time to recover and this seems to be mirrored in the observed slower recovery of brain volumes of these areas.”

The latest findings may have implications for treatment choices, the researchers suggest.

“Many alcohol treatment programs only deal with the withdrawal stage of abstinence from alcohol, that is, the first three days. Based on the current study and others, clinicians should consider recovery programs that provide support for the recovering addict for a minimum of two weeks,” Zahr said. “This study offers recovering alcoholics a sense of hope. Hope that even within two weeks of abstinence, the recovering individual should be able to observe improvements in brain functioning that may allow for better insight and thus ability to remain sober.”

More information

The U.S. National Institutes of Health has more about the effects of alcohol on the brain.