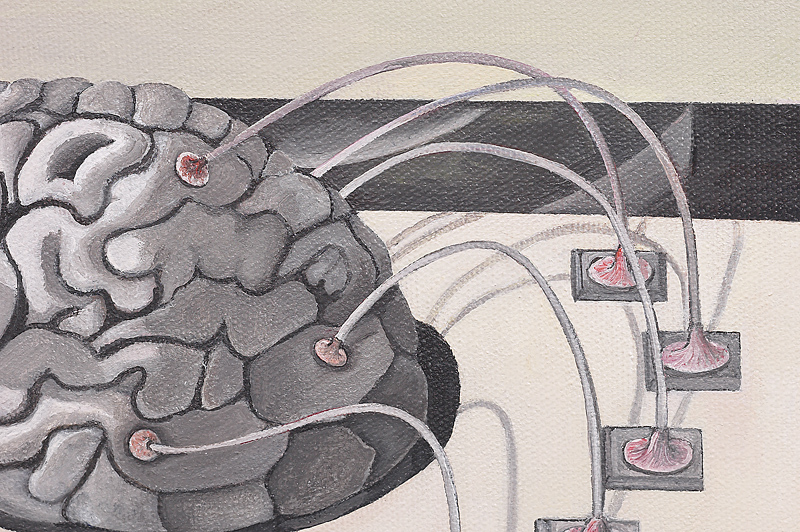

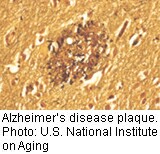

WEDNESDAY, June 12 (HealthDay News) — People with genetic mutations that lead to inherited, early onset Alzheimer’s disease overproduce a longer, stickier form of amyloid beta, the protein fragment that clumps into plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, a small new study has found.

Researchers found that these people make about 20 percent more of a type of amyloid beta — amyloid beta 42 — than family members who do not carry the Alzheimer’s mutation, according to research published in the June 12 edition of Science Translational Medicine.

Further, researchers Rachel Potter at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues found that amyloid beta 42 disappears from cerebrospinal fluid much more quickly than other known forms of amyloid beta, possibly because it is being deposited on plaques in the brain.

Alzheimer’s researchers have long believed that brain plaques created by amyloid beta cause the memory loss and thought impairment that comes with the disease.

This new study does not prove that amyloid plaques cause Alzheimer’s, but it does provide more evidence regarding the way the disease develops and will guide future research into diagnosis and treatment, said Dr. Judy Willis, a neurologist and spokesperson for the American Academy of Neurology.

The mutation occurs in the presenilin gene and has previously been linked to increased production of amyloid beta 42 over amyloid beta 38 and 40, the other types of amyloid beta found in cerebrospinal fluid, the study said.

Earlier studies of the human brain after death and using animal research have suggested that amyloid beta 42 is the most important contributor to Alzheimer’s.

The new study confirms that connection and also quantifies overproduction of amyloid beta 42 in living human brains. The investigators also found that amyloid beta 42 is exchanged and recycled in the body, slowing its exit from the brain.

“The amyloid protein buildup has been hypothesized to correlate with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s by causing neuronal damage, but we do not know what causes the abnormalities of amyloid overproduction and decreased removal,” Willis said.

The findings from the new study “are supportive of abnormal turnover of amyloid occurring in people with the genetic mutation decades before the onset of their symptoms,” she said.

Researchers conducted the study by comparing 11 carriers of mutated presenilin genes with family members who do not have the mutation. They used advanced scanning technology that can “tag” and then track newly created proteins in the body. With this technology, they tracked the production and clearance of amyloid beta 40 and 42 in the participants’ cerebrospinal fluid.

This research gives clinicians a potential “marker” to check when evaluating the Alzheimer’s risk of a person with this genetic mutation, Willis said.

“It’s an earlier way to identify the first associations of Alzheimer’s,” she said. “It appears looking at the spinal fluid may be the first way to diagnose this disease.”

Even though the research focused on a genetic abnormality faced by a very small percentage of early onset Alzheimer’s patients, its new insights into the way amyloid beta is produced and exchanged in the body will help investigations into both early and late onset forms of the disease, said Dean Hartley, director of science initiatives for the Alzheimer’s Association.

“The disease pathology is almost identical, when you look at early Alzheimer’s compared with the more common sporadic forms of Alzheimer’s,” Hartley said. “The plaques and tangles that form are nearly identical.”

The study also identifies amyloid beta 42 as a potential target for future drug trials, he added.

“One of the reasons we’ve not made a shot on goal for clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease is we need to understand more about the disease mechanism for Alzheimer’s,” he said. “There actually have been trials to look at drugs that inhibit [the enzyme that causes the formation of amyloid beta]. They have failed because this particular enzyme doesn’t just work on beta amyloid but on other proteins in the body as well. It wasn’t really a target-specific drug.

“We’re not that far away from clinical trials,” Hartley continued. “The question is whether this target is going to turn out to be a safe target.”

More information

Learn more about Alzheimer’s disease at the Alzheimer’s Association.