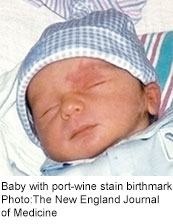

WEDNESDAY, May 8 (HealthDay News) — Researchers say they finally know what causes babies to be born with port-wine stain birthmarks and a rarer but related condition that often leads to lifelong struggles with blindness, seizures and mental disabilities.

In a new study published in the May 8 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine, scientists say a single random change to a single gene after conception causes both the birthmarks, which affect about one in 300 babies, and Sturge-Weber Syndrome, which occurs in about one in 20,000 births.

The change causes a molecular switch that’s normally flipped on and off by chemical messages received by the cell to get stuck in the ‘on’ position.

“It’s great because we have an immediate biochemical understanding of what’s happening, and that means we can immediately move on to the idea of what to do about it,” said Jonathan Pevsner, director of bioinformatics at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore.

“Previously, it was sort of like walking in the dark. We had to settle for treating symptoms and making best guesses,” said study co-author Dr. Anne Comi, director of the Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Hunter Nelson Sturge-Weber Center. “This turns on a light to guide steps for research and treatment, and the direction for where we need to go.”

The discovery marks a milestone for the field of genetics, where advances have only recently made it possible to find these rare “lightning strike” mutations.

It is also a triumph for parents of children with the rare disorder who began saving samples of skin and brain tissue years ago, before the technology was even in place to test them.

“I started laughing. I was just in shock,” said Karen Ball, president and CEO of the Sturge-Weber Foundation, which has more than 5,000 members around the world. “I was just like, ‘Oh, my gosh, it worked.’ It’s a giddy rush of emotions.”

Ball and her husband started the Sturge-Weber Foundation in 1987, after their daughter, Kaelin, was born with the condition.

“When they gave me Kaelin, when she was a baby, she had a birthmark on her whole face,” Ball said. “You feel all kinds of emotions at that moment too.”

Beyond the birthmark, half of Kaelin’s brain had hardened before birth and didn’t work. Pressure was building up in her eyes, threatening her optic nerve. Doctors told the Balls that their daughter would likely have seizures and could lose her vision over time.

“Once I got over the pity party that I had — ‘Oh, she’s never going to do this and she’s never going to do that’ — then we geared up and said, ‘All right, we’re going to find out why this happened and make it better.'”

Ball met Pevsner at a conference sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in 1999. There, doctors said they would need tissue samples if they were to discover the roots of the condition.

Ball began to urge parents to contribute to a collection of samples.

“That was a hard sell for parents, because they didn’t want to scar their baby on top of the birthmark, so you have to walk them through that psychological process [of donating tissue],” she said.

They didn’t yet know what kinds of tests doctors might need to run, so some of the samples were preserved in paraffin wax while others were frozen or stored in saline.

“The donated samples were essential to the success of the research,” Comi said.

For the study, researchers sequenced the entire genome — 3 billion base pairs of DNA — from samples of tissue taken from three different patients. Half of the samples were from affected areas of skin or brain tissue while the other half were from normal, healthy tissue from the same patients.

Out of 700 billion base pairs of DNA, there was only a single spot that was consistently changed between affected and unaffected samples.

“It’s a needle in a million haystacks [to find that],” Pevsner said.

Once they found the change, they searched for it in 97 other samples of patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome or port-wine stains, and healthy patients who didn’t have either.

Nearly all the patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome or port-wine stains had the mutation in affected areas of the skin or brain. Researchers almost never found the mutation on visibly normal skin or in people with neither the birthmark nor the syndrome.

The mutation is in the GNAQ gene, which makes a protein that is critical for cell signaling.

Researchers think that when the mutation happens very early in a baby’s development, it may lead to the more severe Sturge-Weber syndrome. When it happens later, it causes port-wine stains, which can be disfiguring but usually don’t lead to more extensive health issues.

Now that they have identified the mutation, doctors can start to look for drugs that will treat some of the problems it causes. Current treatments for Sturge-Weber aim to control symptoms, but don’t always do the job.

“In half or more of the patients, their seizures are not fully or well-controlled,” Comi said. “We have low-dose aspirin to try to prevent strokes. We’re able to help the children, but we’re certainly not able to prevent all the neurologic and ophthalmologic consequences of the condition.”

Perhaps the most immediate consequence of the discovery may be that it lessens the guilt felt by many parents who believe they somehow caused their children’s condition by passing it to them genetically.

“For some parents, it’s going to be a huge relief,” Ball said. “It’s a huge lodestone that people carry for a while.”

Ball said she didn’t really feel the weight of her own guilt lift until recently, when she heard the news of the discovery.

“I didn’t know if I had caused it,” she said. “But I always felt that if I had caused it, then it was my responsibility to make it right.”

More information

For more information on port-wine stain birthmarks or Sturge-Weber Syndrome, head to the Sturge-Weber Foundation.