SUNDAY, April 7 (HealthDay News) — Researchers applying 21st-century science to investigate a collection of 19th-century medicines discovered that the antique jars held both noxious and promising potions once sold as quick cures for everything from commonplace to dreaded diseases.

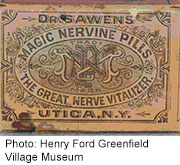

The colorful collection of old and ornate medicine jars was stored in the back halls of the Henry Ford Museum, in Dearborn, Mich., as part of the facility’s “Health Aids” collection.

Mark Benvenuto, a professor of chemistry at the University of Detroit, Mercy, worked with undergraduate students to analyze the contents of 25 of the containers. Using X-ray fluorescence for the solid materials and nuclear magnetic resonance for the liquids, they spent only about five minutes per container to identify each container’s chemical content, he said.

The results of their findings are slated to be presented April 7 at the annual meeting of the American Chemical Society in New Orleans.

The medication labels revealed little about what was inside: Hollister’s Golden Nugget Tablets, Dr. F.G. Johnson’s French Female Pills, Reynolds and Parmley’s Female Health Restorative, and DeBell’s Kidney Pills.

But Benvenuto discovered a wide range of ingredients in the containers, including heavy metals such as mercury, lead and silver; calcium and zinc; manganese and potassium, and arsenic. Five samples contained radioactive thorium.

While the presence of some of the heavy metals may be due to contamination from their storage containers, arsenic and mercury were known to be common treatments for syphilis, Benvenuto said. Lead tastes sweet, so it may have been added to medicine to make it more palatable, he added.

The medications were typically sold by physicians in stores, by mail or in traveling medicine shows, long before clinical trials and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval were required to ensure the safety and effectiveness of treatments, Benvenuto explained. They were called “patent medications,” but the term referred to the fact they were created by individuals and considered to be trade secrets, not officially registered with the U.S. patent office, he noted.

“These medications represent a first step toward the medical establishment we have today,” said Benvenuto. “The doctors who made these medicines were systematically going at trial and error based on what seemed to make people better. Maybe some were just complete shysters and quacks who wanted to make money, but some [of the medicines] were apparently worthwhile.”

Why were such powerful ingredients used in these medications?

Government historian Michael Sappol, of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, explained that the strong treatments were necessary to help a patient believe the medication was having an impact. “Drugs were made to make you experience something so you’d feel healed or treated,” he explained. “The medicine probably wouldn’t have had a healing effect on your body except as a placebo effect.”

And, Benvenuto added, the ornate medicine bottles with elegant lettering and fascinating names probably added to the perceived value of the medication for consumers. “Some were just gorgeous; that possibly added to the perception the drugs worked,” he noted.

While it’s tempting to see these antique medications as quack cures, Sappol said it was important to understand that the ongoing development of these drugs was part of a good physician’s process of testing and evaluating treatments.

“If you went to a regular doctor in 1885 and said you thought you had syphilis, that doctor would probably give you mercury and some other stuff,” he explained. “And a quack doctor might also give you mercury. So you have to be very careful in making the distinction between quack medicine and regular medicine. We all know it’s a fine line.”

Just as physicians in the 19th century responded to consumer demand for quick fixes, doctors today are often sensitive to the same sort of requests, Sappol added. “Doctors now want to know if something worked, and if you say it hasn’t, they try something else. In some ways, the medicine we have now is a legacy of that time,” he said.

Benvenuto suggested that modern consumers shouldn’t be too smug about how the state of medicine today compares to the 19th century.

“I wonder what chemists studying our medications 100 or 200 years from now might think about us,” he said.

The data and conclusions of research presented at medical meetings should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

Learn more about the history of medicine from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.