THURSDAY, March 21 (HealthDay News) — Those convenient, prepackaged meals and snacks for toddlers may contain worrisome levels of salt, U.S. researchers report.

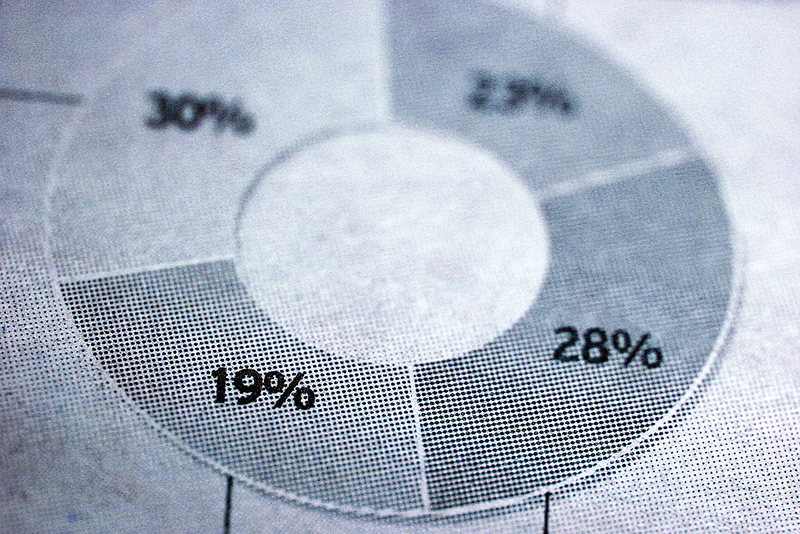

More than three quarters of 90 toddler meals evaluated by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were high in sodium, according to a new study.

Ready-to-eat foods for babies were less alarming, found the experts, who reported on the sodium content of 1,115 products for babies and toddlers using per-serving data from major and private-label brands.

“The products we assessed for babies and infants were relatively low in sodium,” said Joyce Maalouf, a fellow at the CDC division for heart disease and stroke prevention.

“Unfortunately, the toddler food products — meals and snacks — have higher amounts of sodium,” she said. Those products are aimed for kids 1 to 3 years old.

She is scheduled to present the findings Thursday at a American Heart Association meeting in New Orleans.

Eating too much sodium, the main component of salt, can lead to high blood pressure, which is a risk factor for heart disease and stroke.

Moreover, studies have suggested that children’s taste for salt may be reduced if they consume less sodium at a young age, Maalouf said. “Children are not born with a taste for salt,” she noted.

The researchers defined a product as high in sodium if it exceeded 210 milligrams (mg) per serving. The American Heart Association recommends limiting sodium intake to less than 1,500 mg a day, but some toddler meals contained as much as 630 mg per serving — 40 percent of the recommended daily total.

“The toddler meals ranged from 100 milligrams per serving up to 630 milligrams per serving,” Maalouf said. The average was 369 mg, with 71 percent of the meals high in sodium.

The researchers evaluated four toddler savory snacks, such as cheese and crackers, and found they ranged from 70 mg to 310 mg per serving.

Cereal bars for toddlers ranged from zero to 85 mg of sodium per serving. Fruit snacks for toddlers ranged from zero to 60 mg per serving.

Maalouf declined to name products by brand. “The main purpose of the study was to look at food categories, not compare brands,” she said. “Even within the same brand, we had a wide variation of sodium.”

Still, prepackaged macaroni and cheese, cheese and crackers, pasta and chicken, pepperoni pizza and chicken noodle soup typically have high sodium levels, Maalouf added.

The message for parents, Maalouf said, is to read nutrition labels and choose lower-sodium items.

The findings are no surprise to Julia Zumpano, a registered dietitian at the Cleveland Clinic’s department of preventive cardiology. Foods prepackaged for infants tend to be lower in sodium, as they contain just one or two ingredients, often vegetable- or fruit-based, and servings are smaller than those for toddlers.

The popularity of convenience foods — which she defines as “anything in a box, bag, frozen container or can” — has climbed along with the rise in two-income families, she said. Working parents turn to these meals because of time constraints.

To cut down on sodium, she suggested balancing a prepackaged, high-sodium lunch with a healthier, lower-sodium dinner. For snacks, pick fruit, such as an apple, over packaged cheese and crackers. “It’s no less convenient,” she said.

Her guideline for maximum sodium is stricter than that used for the study. “A single food, such as a slice of bead, a serving of cheese, a salad dressing, should be under 140 milligrams,” she said.

Parents can also teach their kids that prepackaged meals and snacks should be enjoyed occasionally but not everyday, she said.

In response to the study finding, Gerber, which makes ready-to-eat baby and toddler foods, said in a statement that it is “proactively reducing sodium levels in our toddler meal options while maintaining the great taste that mothers and children expect.”

In 2011, the company said it reduced sodium in some toddler meals as much as 30 percent. By 2013, it expects to reformulate 80 percent of its toddler meals to have less sodium, according to the statement.

More information

To learn more about sodium labeling, visit the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.