SATURDAY, March 9 (HealthDay News) — Combining the vitamin niacin with a cholesterol-lowering statin drug appears to offer patients no benefit and may also increase side effects, a new study indicates.

It’s a disappointing result from the largest-ever study of niacin for heart patients, which involved almost 26,000 people.

In the study, patients who added the B-vitamin to the statin drug Zocor saw no added benefit in terms of reductions in heart-related death, non-fatal heart attack, stroke, or the need for angioplasty or bypass surgeries.

The study also found that people taking niacin had more incidents of bleeding and/or infections than those who were taking an inactive placebo, according to a team reporting Saturday at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, in San Francisco.

“We are disappointed that these results did not show benefits for our patients,” study lead author Jane Armitage, a professor at the University of Oxford in England, said in a meeting news release. “Niacin has been used for many years in the belief that it would help patients and prevent heart attacks and stroke, but we now know that its adverse side effects outweigh the benefits when used with current treatments.”

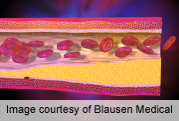

Niacin has long been used to boost levels of “good” HDL cholesterol and decrease levels of “bad” LDL cholesterol and triglycerides (fats) in the blood in people at risk for heart disease and stroke. However, niacin also causes a number of side effects, including flushing of the skin. A drug called laropiprant can reduce the incidence of flushing in people taking niacin.

This new study included patients with narrowing of the arteries. They received either 2 grams of extended-release niacin plus 40 milligrams of laropiprant or matching placebos. All of the patients also took Zocor (simvastatin).

The patients from China, the United Kingdom and Scandinavia were followed for an average of almost four years.

Besides showing no helpful effect on heart health outcomes, the team noted that people taking niacin had about the same amount of heart-related events (13.2 percent) as those who took a placebo instead (13.7 percent).

Side effects were common. As already reported online Feb. 26 in the European Heart Journal, by the end of the study, 25 percent of patients taking niacin plus laropiprant had stopped their treatment, compared with 17 percent of the patients taking a placebo.

“The main reason for patients stopping the treatment was because of adverse side effects, such as itching, rashes, flushing, indigestion, diarrhea, diabetes and muscle problems,” Armitage said at the time in a journal news release. “We found that patients allocated to the experimental treatment were four times more likely to stop for skin-related reasons, and twice as likely to stop because of gastrointestinal problems or diabetes-related problems.”

Patients taking niacin and laropiprant had a more than fourfold increased risk of muscle pain or weakness compared to the placebo group, the team noted.

Did the fault lie with the laropiprant and not niacin? Armitage is doubtful.

She pointed to a prior trial, called AIM-HIGH, which was discontinued early in 2011 when researchers found no benefit to niacin treatment. At the time, some experts said that the smaller population in AIM-HIGH masked any sign of benefit, but Armitage said the new trial’s much bigger study group confirms that niacin probably does not help.

Speaking in February at the time of the journal’s release of niacin’s safety profile, one U.S. expert was less than impressed by niacin’s performance.

The trial “confirms that, for the present moment, there may be little additional benefit with the use of niacin when patients are well treated with the lipid-lowering statin drugs,” said Dr. Kevin Marzo, chief of cardiology at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y.

He said that the results of the new trial, along with those from a prior large study, “now may put the final nail in the coffin on niacin-based strategies to raise HDL and lower cardiovascular events.”

Other tried-and-true approaches may work best, Marzo added. “In addition to statins, our focus should be on continued lifestyle changes such as a Mediterranean diet, complemented with daily exercise,” he said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration had been waiting on the new trial results to decide whether to approve niacin/laropiprant for use against heart disease. But in December 2012, responding to preliminary findings, drug maker Merck said it no longer planned to press for approval from the FDA and in January suspended niacin/laropiprant from markets worldwide.

More information

The U.S. National Institutes of Health outlines steps you can take to reduce heart risks.