MONDAY, Dec. 17 (HealthDay News) — A robotic hand that’s controlled by the thoughts of a woman who is paralyzed from the neck down provides her with an amount of control and movement never before achieved in this type of artificial limb, say the scientists who developed it.

The woman’s prosthetic hand functions nearly the same as a normal hand, according to the University of Pittsburgh team.

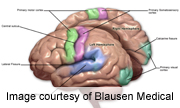

The 52-year-old patient had been diagnosed with a degenerative brain and spinal disease 13 years earlier and eventually became unable to move her arms and legs. In February 2012, the researchers implanted two microelectrode arrays into the woman’s left motor cortex.

A microelectrode array is a device that connects brain cells (neurons) to electronic circuitry. The motor cortex is the part of the brain that initiates movement.

The microelectrode arrays in the woman’s brain were connected to the robotic hand. She then underwent 14 weeks of training to learn how to use the artificial hand, according to an article published online Dec. 17 in The Lancet.

By the second day of training, the woman was able to move the hand freely without the aid of a computer. Over time, she was able to complete more than 91 percent of tasks meant to assess her ability to control the hand, and did the tasks more than 30 seconds quicker than at the start of the training.

The patient’s rapid adaptation to the robotic hand was party due to a new way of connecting her brain to the hand, explained study author Andrew Schwartz.

“In developing mind-controlled prosthetics, one of the biggest challenges has always been how to translate brain signals that indicate limb movement into computer signals that can reliably and accurately control a robotic prosthesis. Most mind-controlled prosthetics have achieved this by an algorithm which involves working through a complex ‘library’ of computer-brain connections,” he said in a journal news release.

“However, we’ve taken a completely different approach here, by using a model-based computer algorithm which closely mimics the way that an unimpaired brain controls limb movement. The result is a prosthetic hand which can be moved far more accurately and naturalistically than previous efforts,” Schwartz explained.

This “brain-machine interface is a remarkable technological and biomedical achievement,” said Gregoire Courtine, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, who wrote an accompanying editorial.

More information

The Society for Neuroscience has more about brain-controlled prosthetics.