WEDNESDAY, June 30 (HealthDay News) — New research suggests the combination of a memory test and a brain scan may best predict the likelihood that an individual with mild cognitive problems will go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), is a condition “in which a person has problems with memory, language or another mental function severe enough to be noticeable to other people and to show up on tests, but not serious enough to interfere with daily life,” according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Although not everyone with MCI will go on to develop Alzheimer’s, the team of researchers noted that some ultimately will. And using these tests in tandem, they said, could increase early intervention among those most at risk.

“Even though it’s true that there aren’t preventive treatments for Alzheimer’s, there are good reasons to want to know early [whether you are developing it],” explained study author Susan M. Landau, a research scientist with the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at the University of California at Berkeley and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“Basically, there are a number of really exciting drugs in the pipeline now that are being tested,” she explained. “It’s overconfident to say it’s just a matter of time, but there’s a huge amount of money and effort going into vaccine-type drugs, drugs that treat the symptoms and all kinds of different mechanisms. So, there’s a lot of promise. And as soon as we have a drug that works, we also hope to have the ability to tell who’s going to benefit from that drug.”

Landau and her colleagues report the findings in the June 30 issue of Neurology.

The study authors spent 1.9 years following the cognitive health of 85 patients participating in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, taking place at 50 medical centers across the United States and Canada.

All had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment but were free of any other major neurological disease, and all were between the ages of 55 and 90.

The team conducted a number of Alzheimer’s assessments that had already been shown to be helpful individually in identifying signs of the disease. For example, an “episodic memory test” that measured patients’ ability to recall a list of words was administered, in addition to MRI brain scans that measured the size of each patient’s hippocampus (the brain region that controls learning and memory).

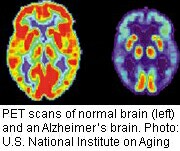

Levels of beta-amyloid — a protein linked to Alzheimer’s — were tallied, and the researchers performed PET brain scans to look for metabolic irregularities also thought to be associated with the disease. Finally, a genetic analysis was conducted to identify which type of APOE gene each patient carried, given that a specific form of the gene has been linked with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s. (The researchers noted that they didn’t include all the exams and tests, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, that are used to look for signs of Alzheimer’s.)

Landau and her team observed that none of the patients reverted to their pre-MCI healthy cognitive state during the course of the nearly two-year study. In fact, 28 of the patients went on to develop Alzheimer’s in that timeframe.

The authors found that PET scans and episodic memory tests turned out to be very effective at predicting Alzheimer’s. In fact, patients with abnormal results on both tests were 12 times more likely to develop the disease than those with normal results.

However, an accompanying editorial — co-authored by Dr. Carol Lippa, director of the Clinical Memory Disorders Program at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia — pointed out that the while the current efforts “dispel some of the mystery” regarding Alzheimer’s progression, it does so by touting the diagnostic benefits of prohibitively expensive PET scans, which are unlikely to be a realistic option for many patients.

Landau agreed that cost is definitely an impediment to widespread PET scan use.

“However, we think where it might be feasible to use imaging is in the process of selecting participants for clinical trials for potential Alzheimer’s drugs,” she said. “Because we want to identify the right people who can ideally benefit from these drugs. So, that’s one possible way it might be a very useful tool.”

“Outside of that, people have imaging done, even though it’s expensive, for lots of medical conditions,” Landau noted. “So if it’s useful enough, it could be promising nevertheless.”

On the latter point, Dr. Gary J. Kennedy, director of the division of geriatric psychiatry at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City, was not so optimistic.

“I’d agree that the PET scan may have applications for the research studies, but for clinical day-to-day diagnosis it’s going to be a rare individual that we send to get it done,” he said. “But the episodic memory test is easy to administer, and it’s not terribly cumbersome. So, it reinforces the value of cognitive testing.”

“But I’d also caution that both tests appeared very, very effective at predicting Alzheimer’s because they were used among a group of selected people among whom you would expect it to be effective,” Kennedy noted. “So if you look at patients visiting the average physician’s office, that predictive power would probably fall off considerably.”

“But it is certainly very important to identify these kinds of tests that have this kind of predictive ability,” he added. “Because even though we don’t currently have much to slow the disease process down at this point, I’d say that a lot can be done as far as helping a person plan ahead.”

More information

For more on early signs of Alzheimer’s visit the Alzheimer’s Association.