FRIDAY, Sept. 28 (HealthDay News) — Most people know the frustration of having a word on the “tip of your tongue” that they simply can’t remember. But that passing nuisance can be an everyday occurrence for someone with aphasia, a communication disorder caused by a stroke or other brain damage that impairs the ability to process language.

About 1 million Americans — roughly one in every 250 — are affected by aphasia, which can also impact reading and writing skills. But how they acquire the problem and how long they’ll endure it differ from person to person, explained Ellayne Ganzfried, a speech-language pathologist and executive director of the National Aphasia Association.

“No two people with aphasia are alike because everyone’s brain responds to the injury in a different way,” Ganzfried said. “About half of people who have aphasia recover quickly, within the first few days. If the symptoms of aphasia last longer than two or three months, a complete recovery is unlikely … [though] some people continue to improve over a period of years and even decades.”

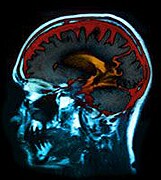

Strokes are the most common cause, followed by head injuries, tumors, migraines or other neurological issues. Depending on the damage to the brain regions controlling language, which are typically in the left hemisphere, the resulting aphasia can be broken into four broad categories:

- Difficulty expressing thoughts through speech or writing

- Difficulty understanding spoken or written language

- Difficulty using the correct names for objects, people, places or events

- Loss of almost all language function, with no ability to speak or understand speech.

“Processing language requires the collaboration of lots of different parts or systems of the brain,” explained Karen Riedel, director of speech-language pathology at the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City. “The whole brain ‘talks’ — the whole brain has something to do with the use of language.”

Because of this, a variety of therapies are used to help people regain as much speech and language as possible. But regardless of the injury, people with aphasia have the best chances for recovery when language therapy begins immediately, Riedel said.

Because aphasia is so variable, a therapy that helps one person might not help another, she noted. Tried-and-true techniques include melodic intonation therapy, which uses melody and rhythm to help improve the ability to retrieve words, and constraint-induced therapy, which forces people to use speech over other communication methods.

But technology, Riedel said, has introduced new language-improvement techniques into the mix over the last few years that are both exciting and fun. Several apps available for iPhone or iPad involve synthetic speech that helps engage those with aphasia in yet another realm of communication.

“Our patients have much more access to different kinds of programs that are computer-based,” she said. “There’s always something new around the corner.”

What remains a constant concern, however, is the misunderstanding many people have of those with language difficulties and how to treat them, Ganzfried and Riedel agreed.

“Many people with aphasia will become socially isolated because of their communication difficulties, which can lead to depression,” Ganzfried said. “There are also many misconceptions about aphasia, including that the person is mentally unstable or under the influence of drugs or alcohol. It’s also extremely frustrating. Imagine knowing what you want to say in your head but you can’t get the words out.”

More information

The U.S. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders has more about aphasia.

A companion article relates a new mom’s battle with aphasia.