WEDNESDAY, Aug. 15 (HealthDay News) — An experimental drug called tofacitinib reduces the symptoms of ulcerative colitis, at least in the short term. The drug appears relatively safe, with few serious side effects, a new study found.

More than three-quarters of those taking the highest dose of the drug — which is given as a pill — had a response to the medication, and 41 percent of these patients achieved a remission, according to the study.

“Tofacitinib . . . affects a group of proteins expressed in the white blood cells. It has a suppressive effect on the immune system,” explained the study’s lead author, Dr. William Sandborn, chief of gastroenterology and head of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at the University of California, San Diego.

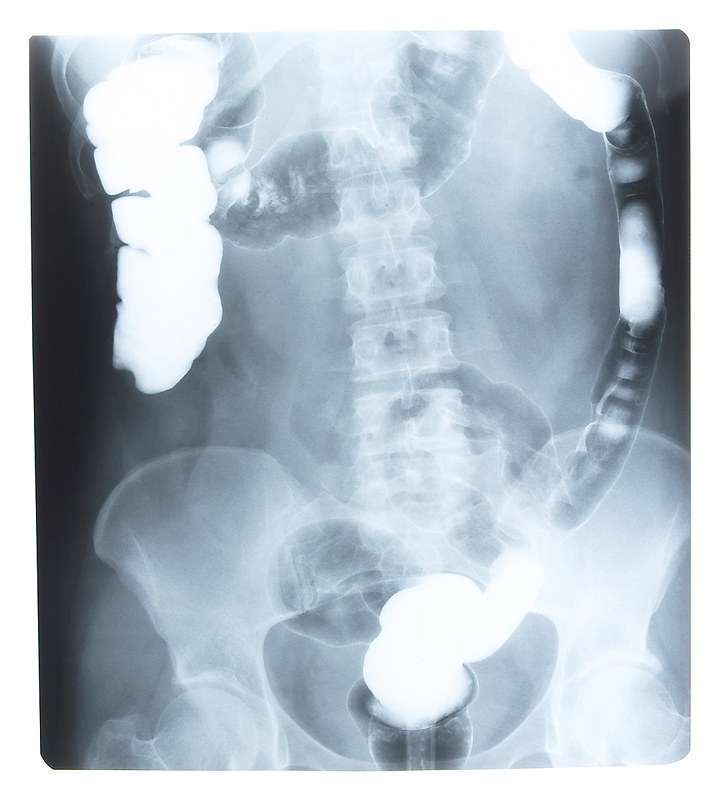

“Ulcerative colitis leads to rectal bleeding, diarrhea and other symptoms that affect a patient’s quality of life. The immune system is attacking the colon in ulcerative colitis, and the theory behind this drug is that you would block the function of the immune system cells that are causing the problems and lead to an improvement in the disease,” Sandborn said.

Results of the study are published in the Aug. 16 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. The drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, provided funding for the study, and Pfizer researchers were involved in the design and implementation of the study, according to Sandborn.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the colon that affects about 700,000 Americans, according to the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The treatment options for the disease are somewhat limited, and the treatments that are available, such as corticosteroids, have many unwanted side effects. Drugs may be used to bring a flare-up of ulcerative colitis into remission or to maintain a remission. Corticosteroids are generally used to induce a remission, but not maintain it, because of their numerous side effects.

Another drug, called infliximab (Remicade), is used to induce and maintain remission in ulcerative colitis. The current study only looked at short-term use of tofacitinib. It’s unclear yet whether the drug could be used for maintenance therapy.

The current study included 194 adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis who were randomly assigned to receive one of four doses of the drug or an inactive placebo twice daily for eight weeks. The drug dosages used were 0.5 milligrams (mg), 3 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg.

The medication was considered to have produced a clinical response if someone had a decrease in their symptom score of 3 or more on a scale of zero to 12, with 12 indicating the most severe disease, or if they had a decrease in their symptoms by 30 percent or more from their baseline score and had an accompanying decrease in rectal bleeding.

Clinical responses occurred in 32 percent, 48 percent, 61 percent and 78 percent of those receiving the medication, respectively, correlating directly with the dose they were taking. The lowest response rate was seen for the 0.5-mg dose, while the highest response was seen in those taking the 15-mg dose. In those taking a placebo, 42 percent had a clinical response.

Remission was achieved by eight weeks in 13 percent, 33 percent, 48 percent and 41 percent of those taking the lowest to highest doses. Ten percent of those on placebo achieved remission, the report noted.

The researchers noted a rise in both good and bad cholesterol that increased as the dose of medication went higher. Three patients had low white blood cell counts, which increases the possibility of infection, according to the study.

“It does seem clear that this drug has a clinical benefit. The 10- to 15-mg twice-a-day dose looks promising for further studies that will look at inducing remission and taking the drug chronically. Can you maintain these benefits over time in a reasonably safe manner?” Sandborn said.

Another expert commented on the study results.

“This drug is taking a new approach and, clearly, at higher doses, it showed a statistically significant effect in terms of response and remission,” said Dr. Michael Poles, a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at New York University School of Medicine in New York City.

But, Poles said he felt the study had a higher rate of adverse events than he likes to see, and he’d like to see long-term results. In addition, he noted, because there are other medications with a longer track record already available, he’d be hesitant to prescribe this new drug until he’d exhausted other options first.

“The drug is worthy of further study, but it may not be the panacea we hoped for,” Poles said.

More information

Learn more about ulcerative colitis from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.