WEDNESDAY, May 26 (HealthDay News) – A congenital heart defect that was typically fatal three decades ago is no longer so deadly, thanks to new technologies and surgical techniques that allow babies to survive well into adulthood, researchers report.

A study in the May 27 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine compares the effectiveness of older and newer versions of devices aimed at fixing incompletely formed hearts. The study finds both performing equally well over three years.

It’s a “landmark” study, “one that we’ve never had before in congenital heart disease,” said Dr. Gail D. Pearson, director of the Adult and Pediatric Cardiac Research Program at the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, which financed the effort.

The study, which compared two devices for keeping oxygen-carrying blood flowing in 549 children born with hearts incapable of doing it alone, has not yet produced definitive results favoring one device over the other. But the research is really just beginning.

“Continuing follow-up will help us sort out the near- and long-term results,” Pearson said.

Study author Dr. Richard G. Ohye, head of the University of Michigan pediatric cardiovascular surgery division, agreed. “Well be able to follow them to adulthood, and they will educate us about the best way to manage them,” he said.

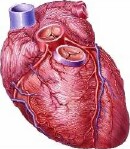

The children in the study were born with hearts that had a nonfunctioning — or nonexistent — left ventricle, the chamber that pumps blood to the body. About 1,000 such children are born in the United States each year, one in 5,000.

Classically, they were fated for quick death. But about 30 years ago, Dr. William Norwood of the Boston Children’s Hospital developed a procedure in which a shunt is implanted so that blood can flow from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up enough oxygen to sustain life. That Norwood procedure, as it is called, is followed by a second operation at 4 to 6 months and a third at 18 to 36 months. If all else fails, a heart transplant can be done.

The new study tested the older shunt, which connects the aorta, the main heart artery, to the lungs pulmonary artery, with a newer model that goes from the heart’s right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

The newer shunt provides better results in the first 12 months — 74 percent survival without a heart transplant, compared to 64 percent with the older model. But there are more complications with the newer model, and the results are about the same with both shunts after 32 months of use, according to preliminary data.

So, the story continues. “We’re continuing to follow these children until they are at least 6 and probably longer,” Pearson said. “We’ll be learning a lot more information over time.”

Even without functioning left ventricles, “many of these individuals live well into adulthood, including middle age,” Pearson said. “Some can live what we think of as normal lives, participating in sports. Others may have more problems.”

“Many have near-normal exercise tolerance and do most of the things children do,” Ohye said.

But they do remain at risk of neurological problems, “because of the things they go through and inborn issues,” he said. For that reason, the neurological development of the children in the study is being monitored, Pearson said, and a report on their mental progress will be issued in time.

Whatever the results, “we have ushered in a new era,” Ohye said. “This is the first randomized trial in congenital heart surgery.”

More information

To learn about congenital heart defects, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.