TUESDAY, March 13 (HealthDay News) — Patients suffering from a strain of E. coli that produces Shiga toxin, which can be deadly, appear to respond to the antibiotic azithromycin (Zithromax), according to German researchers.

Starting in May 2011, an outbreak of Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli infected nearly 4,000 people in Germany, more than 800 of whom had confirmed cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which causes red blood cells to break apart, resulting in kidney failure.

Current treatment discourages using antibiotics for Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli because it could increase the risk for HUS, the researchers note.

“The successful decolonization of long-term carriers of the German outbreak strain is an important finding, as the legal authorities in many countries restrict long-term carriers in their social or working life,” said lead researcher Dr. Johannes Knobloch, of the institute of medical microbiology and hygiene at the University of Lubeck. “However, decolonization by azithromycin should be investigated in further studies for other E. coli strains.”

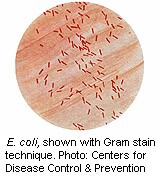

E. coli can cause persistent diarrhea, and it can be spread by those infected through person-to-person contact.

The German outbreak was a mix of E. coli strains O157 and O104 (or enteroaggregative E. coli), both investigated in the new study, which was published in the March 14 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association. “For the treatment of one strain — enteroaggregative E. coli — azithromycin is one of the antibiotics of choice,” Knobloch said.

The study reports on 65 infected patients — some with HUS — who were followed for almost 40 days after showing initial symptoms. Among these patients, 22 were treated with azithromycin starting almost 12 days after their symptoms began; the others were not.

Knobloch’s team found that there were significantly fewer carriers of E. coli among those who took azithromycin, compared to those who didn’t.

Twenty-one days after starting treatment, nearly 32 percent of those taking azithromycin still carried the bacteria, compared with almost 84 percent of those not treated, they found.

After about one month, only 4.5 percent of those who received azithromycin still had the bacteria, compared with more than 81 percent of those who were not treated, and at 35 days none of the patients in the treated group had the bacteria.

In addition, all the treated patients remained bacteria-free after two weeks of antibiotic treatment, the researchers noted. However, 25 of the 43 untreated patients still carried the bacteria 42 days after their symptoms started.

Based on the successful use of azithromycin, it was decided to provide the drug to the 15 patients who still had symptoms.

After receiving azithromycin treatment, these patients no longer carried the bacteria. Moreover, there were no signs of HUS among any of the patients who took the antibiotic, the researchers said.

“This is a small study, but since other antibiotics activate the Shiga toxin, this is a revealing study,” said Dr. Marc Siegel, an associate professor of medicine at New York University in New York City. “Azithromycin may well be the preferred antibiotic when you suspect an aggressive E. coli or a toxic E. coli.”

Another expert, Hugh Pennington, emeritus professor of bacteriology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, is more cautious.

This finding is “not surprising, but relevance to E. coli O157 is far from certain,” he said. The O157 strain of E. coli is particularly severe and also produces the Shiga toxin that often leads to hemolytic uremic syndrome.

“Neither does it help much regarding the issue of antibiotic use increasing the frequency of hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by E. coli O157,” Pennington said. “The issue here, of course, is not whether antibiotics help after hemolytic uremic syndrome has developed, but whether they help to induce it. The jury is still out.”

More information

For more about E. coli, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.