WEDNESDAY, Sept. 21 (HealthDay News) — An experimental drug may offer a thin ray of hope to people suffering from the rapidly fatal lung disease known as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The compound, currently known only as BIBF 1120, seems to slow the disease, decrease exacerbations and improve quality of life for patients, according to a study funded by the drug’s maker, Boehringer Ingelheim, that is published in the Sept. 22 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It improves the course of disease and, in my opinion, it’s the first drug to significantly ameliorate the really devastating progression of the disease,” said Dr. Norman Edelman, chief medical officer for the American Lung Association, who noted that current treatments for the disease “are almost desperation attempts. There’s very little evidence they work.”

“The authors don’t claim [BIBF 1120] is going to reverse the disease. They claim it’s going to slow it down, but even that is a major factor,” added Dr. Hormoz Ashtyani, director of pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine at Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey.

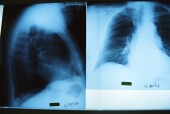

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) involves a relentless stiffening of the lungs due to overproduction of collagen, the “cement” that holds lung tissue together, explained Ashtyani.

Patients with IPF usually die within two to three years of diagnosis. While the disease used to be considered relatively rare, Edelman noted that doctors have been noticing an uptick in recent years, especially among older men.

One reason researchers consider BIBF 1120 so promising is because it is “biologically plausible,” said Edelman, who is also a professor of medicine at Stony Brook University in New York.

The drug inhibits tyrosine kinase receptors that are known to promote fibrosis, or lung scarring, and was successful in doing just that in an earlier study involving rats.

“It’s not a shot in the dark. The biology of this kind of molecule makes sense to use in this disease,” Edelman said.

In this randomized, controlled, phase 2 trial, researchers compared four different doses of BIBF 1120 — 50 milligrams (mg), 100 mg, 200 mg or 300 mg a day — with a placebo in 432 patients.

At the end of a year, patients receiving the highest dose of BIBF 1120 saw their lung function improve by more than two-thirds. They also experienced fewer exacerbations.

There were also some improvements in the 200-mg group.

Unfortunately, some patients taking the highest dose did drop out of the study because of gastrointestinal side effects, as well as liver problems.

The study was not specifically designed to look at mortality, said study author Dr. Luca Richeldi, director of the Center for Rare Lung Diseases at University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Policlinico Hospital in Italy, but there were fewer deaths due to respiratory causes in both the 200-mg and 300-mg groups compared with placebo. Overall, however, there was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

Two phase 3 trials on BIBF 1120 are currently underway, with results expected in the first half of 2014, said Richeldi.

“It will be interesting to see how this turns out in [further] clinical trials,” said Dr. Len Horovitz, a pulmonary specialist with Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City.

More information

To learn more about IPF, visit the Coalition for Pulmonary Fibrosis.