WEDNESDAY, July 20 (HealthDay News) — Inherited forms of Alzheimer’s disease may be detectable up to two decades before problems with memory and thinking develop, according to new research.

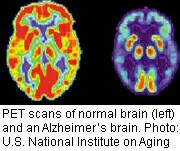

The findings are significant because by the time dementia symptoms appear, the disease has severely damaged the brain, making it nearly impossible to restore a patient’s mental abilities or memories, the study authors noted.

“We want to prevent damage and loss of brain cells by intervening early in the disease process — even before outward symptoms are evident, because by then it may be too late,” Dr. Randall Bateman, Alzheimer’s researcher and physician at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and an associate director of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN), an international study of inherited forms of Alzheimer’s, said in a university news release.

DIAN researchers are following members of families who have mutations in one of three genes: amyloid precursor protein; presenilin 1; or presenilin 2. People with these mutations will develop Alzheimer’s disease early, between their 30s and their 50s, research has shown.

The age of disease onset among study participants could be predicted by referencing their parents. For instance, if a parent developed dementia at the age of 50 years, a child who inherited the mutation would be expected to develop dementia at roughly the same age. As a result, scientists are able to compile detailed chronologies of disease progression, covering the many years Alzheimer’s is active in people’s brains, although symptoms are not yet visible.

Initial results of the study confirm and expand on previous research, which suggested that certain changes in spinal fluid could be detected years before dementia.

“Based on what we see in our population, brain chemistry changes can be detected up to 20 years before the expected age of symptomatic onset,” said Bateman. “These Alzheimer’s-related changes can be specifically targeted for prevention trials in patients with inherited forms of Alzheimer’s.”

The researchers noted, however, clinical trials for the prevention of Alzheimer’s among DIAN participants could carry risks.

“New treatments may have risks, so to treat patients prior to symptoms we must be sure that we have a firm grasp on who will develop Alzheimer’s dementia,” DIAN director Dr. John C. Morris, Harvey A. and Dorismae Hacker Friedman Professor of Neurology at Washington University, concluded in the news release. “If we can find a way to delay or prevent dementia symptoms in DIAN participants, that would be a tremendous success story and very helpful in our efforts to treat the much more common sporadic form of the illness.”

The study was slated for presentation Wednesday at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Paris.

Because this study was presented at a medical meeting, the data and conclusions should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

The U.S. National Institute on Aging has more on Alzheimer’s disease genetics.