THURSDAY, June 30 (HealthDay News) — You’re probably familiar with how easy it is to remember things that never happened, especially if you’re around people who recall things the same way.

British and Israeli researchers used a novel false-memory test and brain-scanning technology to find out how that happens.

About 70 percent of those who took part in the test believed the implanted memories — and certain parts of their brains tended to be more active as they did so, the researchers reported in the July 1 issue of Science.

“Social influence can efficiently manipulate existing memory traces, often creating long-lasting false memories,” said study lead author Micah Edelson. The brain appears to do this by activating regions that control emotions, social interactions and memory processing, he added.

“To create the false memories, we had small groups of participants watch a documentary, and then we tested their individual memories of the film. We also asked them how sure they were that each answer they gave was correct,” said Edelson, a graduate student at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Later, the researchers tried to promote false answers through the use of group influence “to change . . . confident correct answers to incorrect ones.”

Almost 70 percent of the time, the people in the study fell for a false memory and believed it. Of those, about 40 percent kept on remembering the false memory.

The findings of the research, which also involved the Wellcome Trust Center for NeuroImaging at University College London, are relevant to aspects of real life such as the legal system, where eyewitness accounts often sway juries, Edelson said.

The key to the experiment was “the manipulation of social influence,” said Washington University in St. Louis psychology professor Henry L. Roediger III, who co-wrote a commentary accompanying the study. “When subjects in the experiment saw that other people had responded in one way, they tended to conform and respond the same way.”

No one was immune to suggestions of false memories, Edelson said, although some were better able to stick with reality than others.

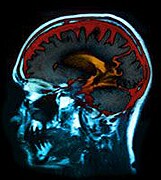

The scans showed that the amygdala and hippocampus areas of the brains were more active in those who believed false memories over time. The hippocampus affects memory, Edelson said, while the amygdala “probably plays a critical role because it is perfectly situated . . . to mediate between the brain’s emotional-social and memory processing systems.”

What does all this mean for daily life?

Edelson said it could play a role in legal cases where eyewitnesses to an event talk to each other about what happened. And it’s possible but not proven, he added, that the effects of group-think on the memories of children — who “are very prone to social influence” — may be greater than on adults.

More information

For more about memory, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.