THURSDAY, April 14 (HealthDay News) — Suicides in the United States appear to increase in hard times and decrease during years of prosperity, according to a new government report.

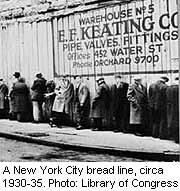

The image of people jumping from windows after the stock market crash of 1929 graphically illustrates the pattern detected by researchers from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The overall suicide rate rises and falls in connection with the economy,” said lead researcher Feijun Luo, a health economist in the division of violence prevention at the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

“The strongest association between business cycles and suicides was among working-age people 25 to 64 years old,” he said.

Co-author Dr. Alexander E. Crosby, a medical epidemiologist in the division of violence prevention at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, said economic hardship may trigger suicidal impulses in those already at risk of killing themselves.

“Suicide results from an interaction of a number of different factors,” Crosby said. “Other studies have shown there is an association between suicide and unemployment, suicide and economic issues, and it can make vulnerable people more prone to be at risk for suicidal behavior,” he said.

The report is published online April 14 in the American Journal of Public Health.

The researchers found suicide rates spiked during the Great Depression (1929-1933), at the end of the New Deal (1937-1938), during the oil crisis of 1973-1975, and the double-dip recession of 1980-1982.

But fewer people killed themselves during periods of economic expansion, such as the World War II years (1939-1945) and between 1991 and 2001, when the economy grew rapidly and unemployment was low.

During the Great Depression, the suicide rate jumped from 18.0 per 100,000 in 1928 to 22.1 per 100,000 in 1932, which was an all-time high. The 22.8 percent increase over that four-year period was a record, according to the report.

Suicide rates were lowest in 2000, when times were booming, the researchers added.

To prevent economy-related suicides during economic downturns, communities might want to target programs toward working-age people, Crosby suggested. “Communities can have more support for those age groups that might be laid off,” he said.

Providing job training, skills training and developing suicide prevention efforts “might be things communities could do,” Crosby added.

Commenting on the study, M. David Rudd, dean of the College of Social and Behavioral Science at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, said that these “interesting findings confirm what many have been thinking from an anecdotal perspective over the last several years.”

Rudd agreed that those most likely to kill themselves in bad economic times are those already at risk of suicide.

“It’s fairly well established that upwards of 90 percent of those taking their own lives suffer from a diagnosable mental illness at the time, with the overwhelming majority not being in active treatment,” he said.

The difference in impact across age groups is not a surprise, given that those hardest hit face the most pressing economic demands, Rudd added. The youngest and oldest groups probably experience relatively less economic pressure, he pointed out.

“Prevention efforts need to focus on recognition and more effective response to psychiatric illness, particularly in primary care settings,” he said.

More information

For more information on suicide, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.