TUESDAY, April 12 (HealthDay News) — Scientists are rearranging the genetic information of certain dogs to make the coding human-like as a way to learn more about the genetic causes in people of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer that begins in the cells of the immune system.

Humans and dogs have a similar genetic makeup and share the same types of cancers, including lymphoma. In purebred dogs of the same breed, however, there are fewer genetic variations than in humans, making it simpler to locate areas of the canine chromosomes that may be involved with cancer.

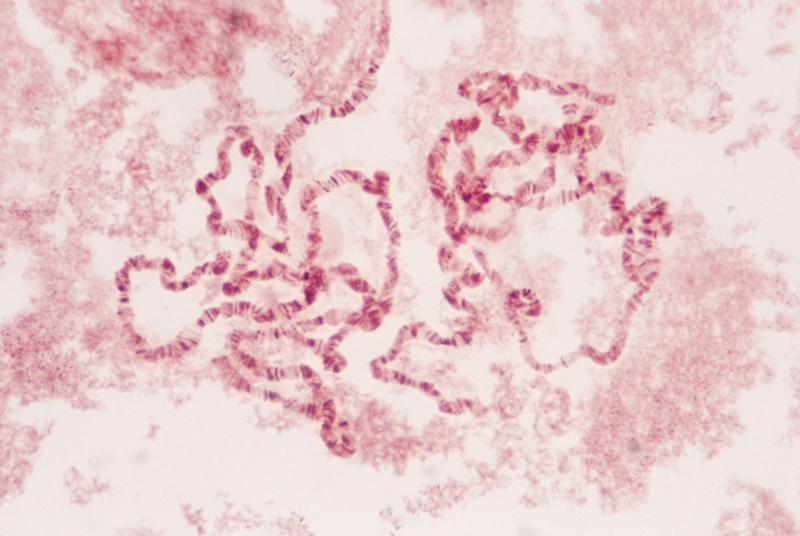

In a new study, North Carolina State University researchers gathered genetic information from dogs with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and then rearranged, or recoded, the genomes of the dogs into human configuration.

The recoded dog genomes were then compared with the genomes of people with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma to identify chromosomes involved in the cancer in both humans and dogs.

“This is the first time that we were able to compare this information from dogs with lymphoma directly with existing data from human patients diagnosed with the equivalent cancer and using the same technique,” lead author Rachael Thomas, a research assistant professor of molecular biomedical sciences at N.C. State, said in a university news release.

She and her colleagues found that dogs and humans share only a few genes that are involved with lymphoma. Previous research had suggested that numerous genes in humans may be associated with lymphoma.

The researchers said that the new findings should help narrow the search for the genes most likely to cause lymphoma in people.

“In essence, we stripped the background noise from the human data,” Matthew Breen, a professor of genomics, said in the news release. “Lymphoma genomics is a lot more complex in human patients than in dog patients. This study tells us that, while both humans and dogs have comparable disease at the clinical and cellular level, the genetic changes associated with the same cancers are much less complex in the dog. This suggests that maybe there is a lot of genetic noise in the human cancers that is not an essential component of the process.

“While human studies have been looking in numerous places in the genome, the dog data indicate we need to focus on what’s shared, and these are very few regions,” Breen said.

The study was published online in Leukemia and Lymphoma.

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more about non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.