TUESDAY, March 29 (HealthDay News) — If you’re looking to lose those extra pounds, you should probably add reducing stress and getting the right amount of sleep to the list, say researchers from Kaiser Permanente’s Center for Health Research in Portland.

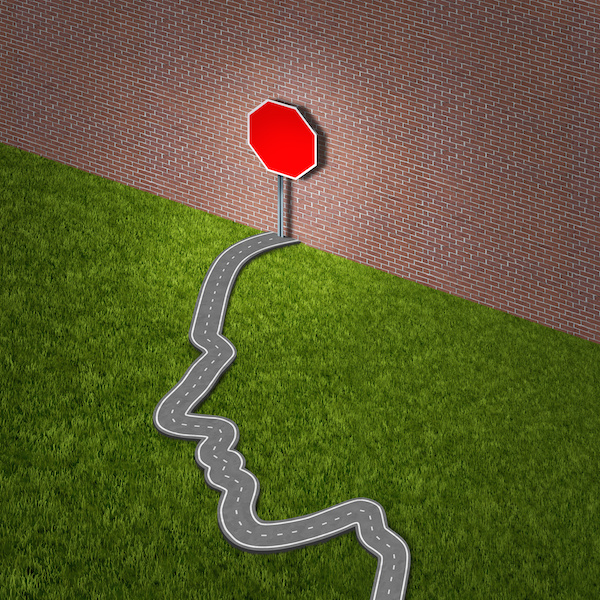

In fact, although diet and exercise are the usual prescription for dropping pounds, high stress and too little sleep (or too much of it) can hinder weight loss even when people are on a diet, the researchers report.

“We found that people who got more than six but less than eight hours of sleep, and who reported the lowest levels of stress, had the most success in a weight-loss program,” said study author Dr. Charles Elder.

Elder speculates if you are sleeping less or more than recommended and if your stress levels are high, you will not be able to focus on making behavioral changes.

These factors may also have a biological impact, he added.

“If you want to lose weight, things that will help you include reducing stress and getting the right amount of sleep,” Elder said.

The report, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, is published in the March 29 online edition of the International Journal of Obesity.

In this two-step trial, 472 obese adults were first counseled about lifestyle changes over a 26-week period. Recommendations included cutting 500 calories a day, eating a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains by following the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet approach, and exercising at least three hours a week.

In addition, the researchers asked the participants questions about sleep time, depression, insomnia, screen time and stress.

During this part of the trial, the participants lost an average of almost 14 pounds. The 60 percent of the participants who lost at least 10 pounds went on to take part in the next phase of the trial. Those in the second phase of the trial continued their diet and exercise program.

Elder’s team found the right amount of sleep and stress reduction at the start of the trial predicted successful weight loss. Lower stress by itself predicted more weight loss during the first phase of the trial, they added.

Declines in stress and depression were also important in continuing to lose weight during both phases of the trial, as were exercise minutes and keeping food diaries, Elder’s group found.

Dr. David L. Katz, director of the Prevention Research Center at Yale University School of Medicine, said that “while we often tend to look at health one condition at a time, the reality is that health is best viewed holistically.”

“People who are healthy and vital tend to be healthy and vital not because of any one factor, but because of many. And the factors that promote health — eating well, being active, not smoking, sleeping enough, controlling stress, to name a few –promote all aspects of health,” he added.

This study shows that people are more likely to lose weight when not impeded by sleep deprivation, stress or depression, he said.

“Anyone who has ever tried to lose weight probably could have said much the same from personal experience. Similarly, weight loss reduced stress and depression. This, too, is suggested by sense and common experience, as it is affirmed by the science reported here,” Katz said.

The important message is that weight loss should not be looked at with tunnel vision, Katz said.

“Improving sleep may be as important to lasting weight control efforts as modifying diet or exercise. Managing stress is about physical health, as well as mental health. This study encourages weight loss in a more holistic context,” he said.

Another study presented earlier this month at the American Heart Association scientific sessions held in Atlanta found that people of normal weight eat more when they sleep less.

Columbia University researchers discovered that sleep-deprived adults ate almost 300 calories more a day on average than those who got enough sleep. And the extra calories mostly came from saturated fat, which can spell trouble for waistlines.

The researchers came to their conclusions — which should be considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal — after following 13 men and 13 women of normal weight. They monitored the eating habits of the participants as they spent six days sleeping four hours a night and then six days sleeping nine hours a night (or the reverse).

“If sustained, the dietary choices made by people undergoing short sleep could predispose them to obesity and increased risk of cardiovascular disease,” the researchers wrote in an American Heart Association news release.

More information

For more information on obesity, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.