MONDAY, March 28 (HealthDay News) — Teens who undergo gastric bypass weight loss surgery can expect to have a decline in bone mass, just as adults do, according to a new study.

Two years after the surgery, the bone mineral content of the 61 obese teens studied had declined, on average, by 7.4 percent, said Dr. Anne-Marie Kaulfers, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of South Alabama.

“At the moment, I do not think there is cause for alarm,” Kaulfers said of the study findings. That’s because the teens, who averaged 17 years old, still had bone mass within the normal range, she said. They had started with above-average bone mass for their age and gender.

The findings are reported online March 28 in the journal Pediatrics.

Kaulfers and her colleagues decided to study the teens because a loss of bone mineral content during adolescence, when they should be approaching peak bone mass, could potentially compromise future bone health.

Studies of adults have also found that their bone mass declines after the surgery.

Kaulfers did the study while at Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati. Some of the participants were part of the Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Consortium supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

All of the teens, 10 boys and 51 girls, had gastric bypass, a procedure in which the stomach is reduced from the size of a football to that of a golf ball.

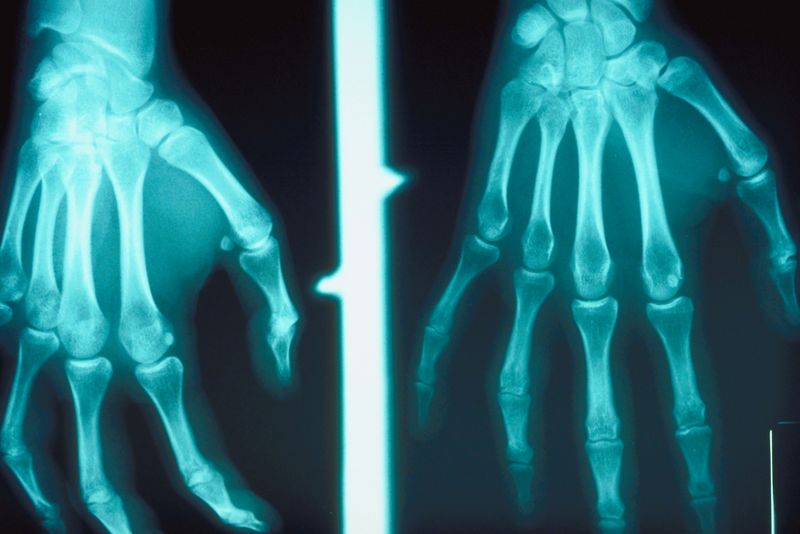

The researchers measured bone mineral content and density by dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA). When possible, measurements were taken before surgery and then every three to six months after the surgery for up to two years.

Called a “z score,” the teens’ average bone mineral density scores decreased from 1.5 to 0.1. A z score of 0 is normal, Kaulfers said, and a negative score would reflect low bone density.

Though what happens beyond two years is unknown, Kaulfers said that the bone loss appears to be offset by the benefits of the surgery, such as reducing the likelihood that the teens would develop diabetes.

But teens who have the surgery need to be closely monitored, she cautioned.

The bone loss after weight loss surgery may be due to the weight loss itself, she said, or it could stem from other factors, such as hormonal changes.

“I think the note of caution [about long-term follow-up] is very good,” said Dr. Robin Blackstone, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and a bariatric surgeon in Scottsdale, Ariz.

She said she orders annual bone scans for her teen patients.

Dr. Neil Roth, an orthopaedic surgeon at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, cited limitations to the research, which the study also noted.

“A fairly high percent didn’t have a DXA scan before the study because they couldn’t fit into the scanner” so there was no information on their bone status before the surgery, he said. That was the case for 64 percent, according to the study.

The long-term effect on bone health is unfolding for teens, so until more research is in, he said, proceeding with caution would be wise.

“Make sure, as with any procedure, you exhaust your conservative measures first before you embark on something that is life-altering.”

More information

The U.S. National Library of Medicine has more on gastric bypass surgery.