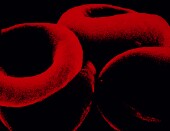

WEDNESDAY, Dec. 16 (HealthDay News) — Hoping to improve on nature, researchers have built and tested synthetic versions of the blood-clotting cells called platelets, to be used in trauma or other cases where blood just won’t stop flowing.

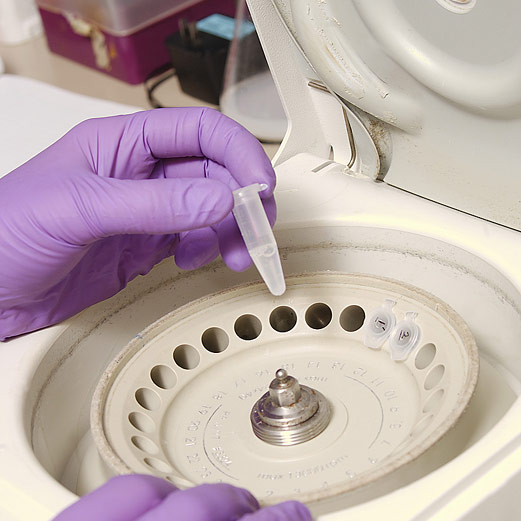

“We start by making a core, with material that is used in degradable stitches, which dissolve in the body,” said Erin B. Lavik, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University, and lead author of a report published Dec. 16 in Science Translational Medicine. “Then we attach a polymer that is soluble in water and is used in the pharmaceutical industry. Then we attach a molecule that interacts with activated platelets and helps them clot more quickly.”

The hope is that the artificial platelets can replace or augment the activity of the currently used clotting medication, known as factor VIIa, Lavik explained.

Factor VIIa is a protein that plays a central role in blood clotting. A genetically engineered version of the protein is now available for medical use. It was introduced for use in people with hemophilia, a genetic condition in which normal clotting does not occur, and it is being increasingly used against uncontrollable hemorrhage.

But factor VIIa must be kept in refrigerated form and has a short shelf life, Lavik said. And it cannot be used for head or spinal cord injuries, for fear of complications.

“The reason we developed this synthetic platelet is that it is stable at all temperatures,” Lavik said. “It is a fine powder that can be administered intravenously. The faster you can control bleeding, the better the outcome.”

In animal tests, injured rats given injections of the artificial platelets stopped bleeding in half the time of those that went untreated. Rats that got injections 20 seconds after an injury stopped bleeding in 23 percent less time than untreated rats.

“We also did head-to-head comparisons with factor VIIa,” Lavik said. “When the artificial platelets were introduced, bleeding was reduced even more.” The artificial platelets induced clotting 25 percent faster than factor VIIa, the report said.

However, a long series of tests lie ahead before the artificial platelets can enter routine medical practice, Lavik said. “The next step would be an animal model that most closely mimics human injury,” she said. “We have to move up to larger animals. Pigs are most commonly used.”

Financial help is also needed. “We have applied to federal and non-federal groups for funding,” Lavik said. She is hoping for support from a pharmaceutical company because “ultimately, you have to think about making it commercially viable.”

“We have just started having those conversations,” Lavik said. “Now that we have published this paper, we hope we can generate some interest.”

A critical point is convincing the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that artificial platelets would have a useful medical application, Lavik said. Convincing the FDA would start with data from future animal studies. “Assuming that it replicates what we have seen so far, then we would talk with the FDA,” she said. “There is no use estimating our chance of success until we see that data and talk with them.”

“Anything new that would be safe to use with someone who has ongoing hemorrhage would be useful in a trauma center,” added Dr. Michael Craun, trauma medical director at Scott and White Memorial Hospital in Temple, Texas. “We really have problems now with people who have major injuries.”

Another expert agreed. “Any compound or device that can stem hemorrhage in patients can be helpful if the risk-benefit ratio is favorable,” said Dr. Brian Harbrecht, director of trauma at the University of Louisville.

But he and Craun also stressed the early nature of the work.

“A lot more investigation needs to go into this particular product to see if it is clinically applicable or not,” Harbrecht said. “That requires years and years of more precise work.”

The new report described “preliminary experiments with rats only,” Craun added, and there are questions about safety, cost and technology still to be answered.

More information

To learn how platelets work and what can happen if they don’t work properly, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.